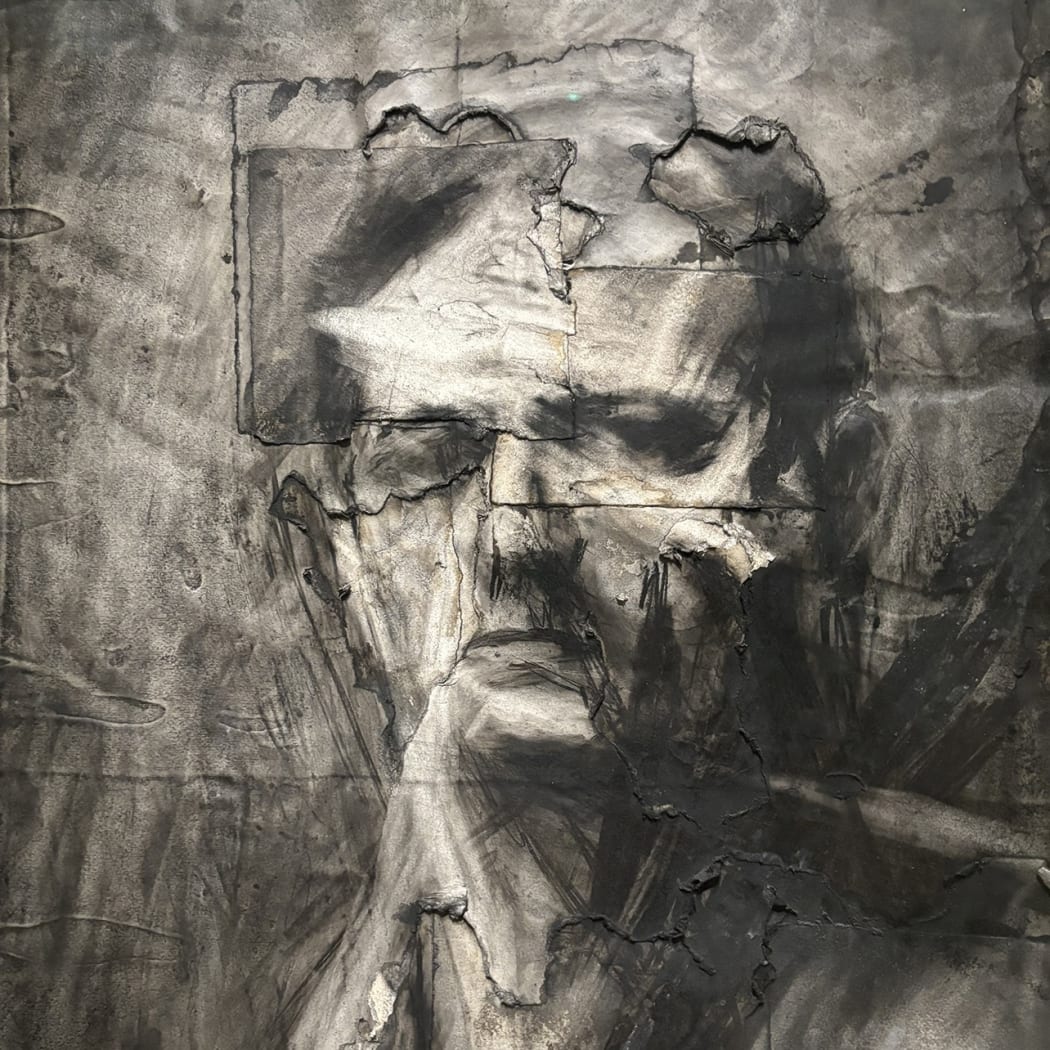

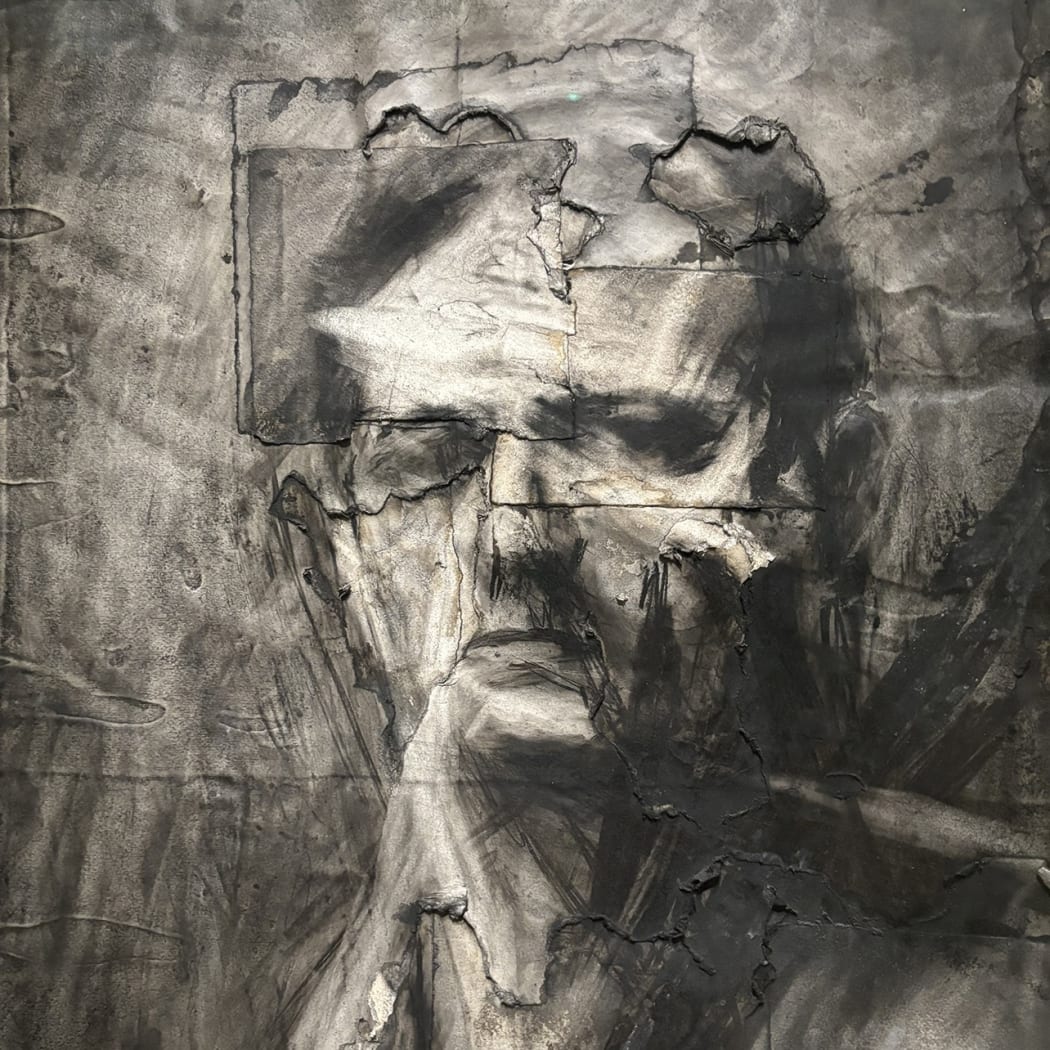

Detail of Frank Auerbach self-portrait 1958

Charcoal Heads has been heavily trailed on social media. Auerbach’s gimlet gaze stares out from his 1958 self-portrait on every post. For such a concise exhibition, it packs a punch. It consists of just two rooms of potent charcoal portraits made early in the artist’s career between the late 50s and early 60s.

London was still a shattered city in the late 1950s, the second world war had left its streets in a disordered patchwork of bomb sites and partial streetscapes. The backs and sides of buildings ripped open, different architectural eras truncated violently by explosive force, continuity erased. Collected in these two galleries Auerbach’s drawings shine out from the dreariness of post war Britain. Rationing had only recently been lifted in 1954. His sitters look lean and spare, their eyes averted. As a Jewish immigrant escaping Nazi persecution, it is apposite that this is the moment we are being confronted with the significance of Auerbach's work, an artist who although originally from Germany, has made his contribution over the last seventy years, enriching British art immeasurably.

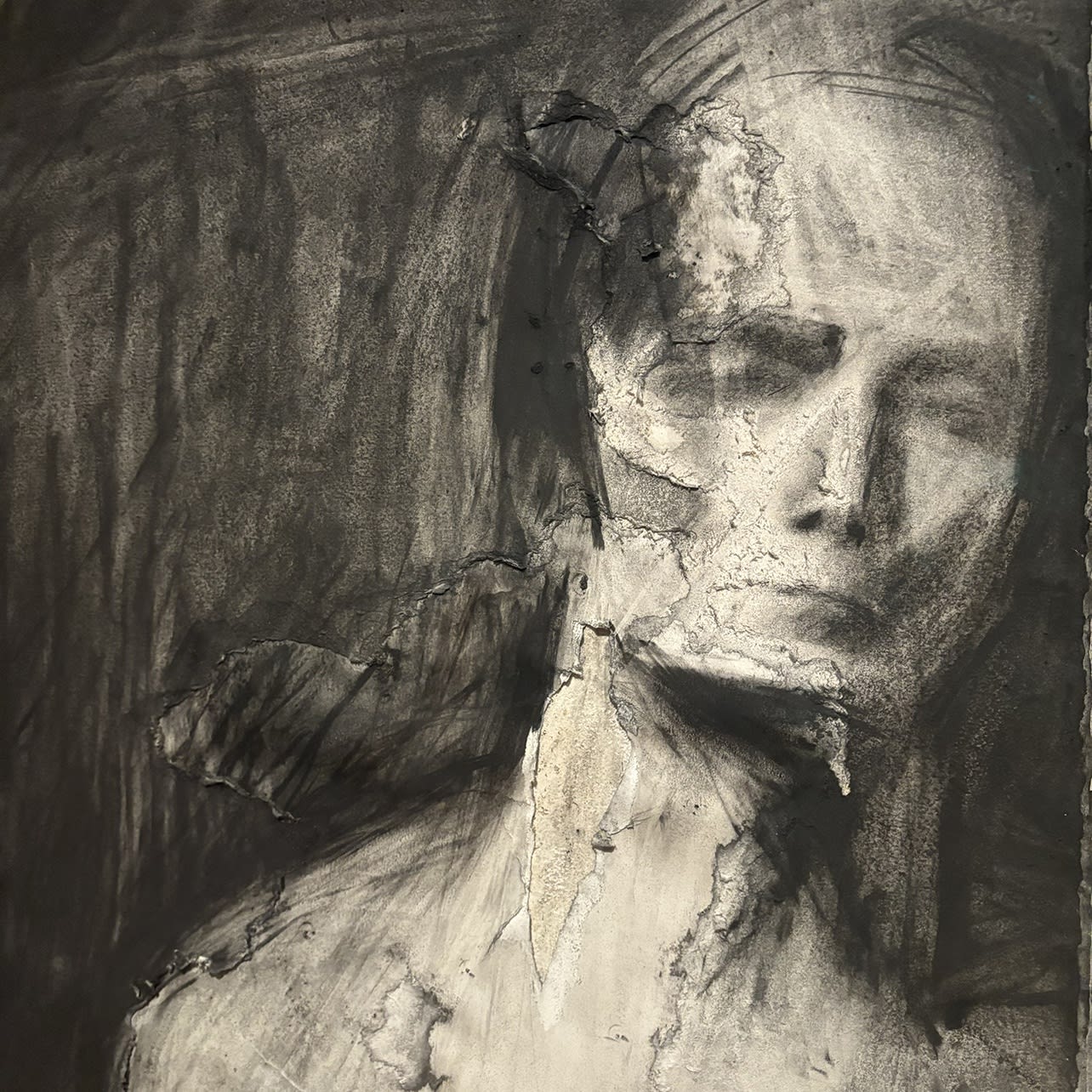

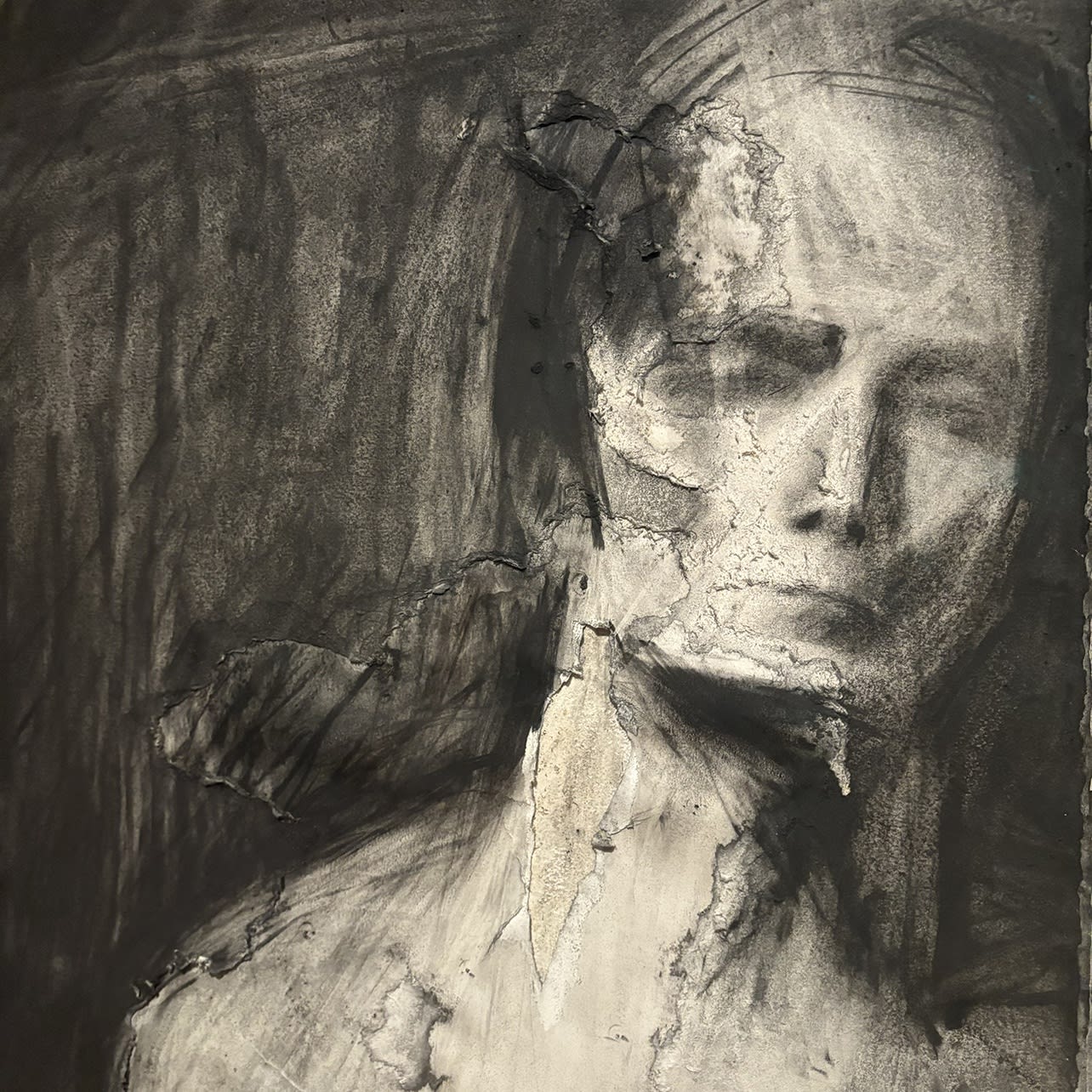

Detail of Head of E.O.W (Stella West) 1960 by Frank Auerbach

Head of E.O.W III (Stella West) 1960 by Frank Auerbach

Each drawing is part of a sequence. Among them canvases punctuate each sequence of charcoal drawings, depicting the same sitter, with the exception of Julia Wolstenholme (who later became the artist’s first wife). The heavily encrusted surfaces of Auerbach’s paintings are usually the focus of our attention and yet in this instance the drawings really are the stars of the show.

The portraits in the first room depict fellow painter Leon Kossoff, and Stella West (E.O.W) who the artist met while both were acting in a play. There is another series of four drawings of Stella West in the second room. Viewing the drawings in relation to each other is a revelation. Each one has been intensely worked, burnished by weeks of layering of charcoal or chalk and the artists extensive use of the rubber, to remove every trace of work at the end of each session. Starting again, each sitting until he reached a satisfactory outcome. This act of erasure has lent the battle-scarred surfaces of the paper a physical presence.

The paper surfaces wear through as Auerbach’s abrasive technique takes its toll. The holes were repaired with a ‘make do and mend’ approach, placing patches of paper over the most worn areas. The glue pushes up behind the patches leaving a trace, where the repair has been subsumed into the existing proportions of the sheet. He has applied the next layer of charcoal over the joins, built up in a haphazard grid underpinning the drawn image. The effect is to make the viewer aware of the process and the longevity of each sitting. Each carefully constructed image took shape over weeks, patched up, new bits inserted like the new buildings that replaced the damage done to London's streets. The light seems to come from within, developed like an early daguerreotype or photograph, the sharpness of the angles of their features revealed by shafts of light.

About the author

Paul Barratt

Paul Barratt started working in contemporary art galleries in 1989, having graduated in Fine Art from Goldmsith’s, London University. He initially worked at Anthony d’Offay Gallery, one of the contemporary art dealers, who dominated the London art market in the 80s and 90s. He was approached by the Lisson Gallery to be gallery manager for the influential art dealer Nicholas Logsdail. This was followed by a short period in New York at Gladstone Gallery, to work for visionary art dealer Barbara Gladstone, working with the artist and filmmaker Matthew Barney.

On his return to London, Paul secured a place on the postgraduate curatorial course at the Royal College of Art, to complete an MA. After graduation in 2001, he worked as an independent curator on several projects in Oslo, London, Brighton and Basel, before joining Paul Vater at his design agency Sugarfree in 2004. He has worked with Paul ever since.